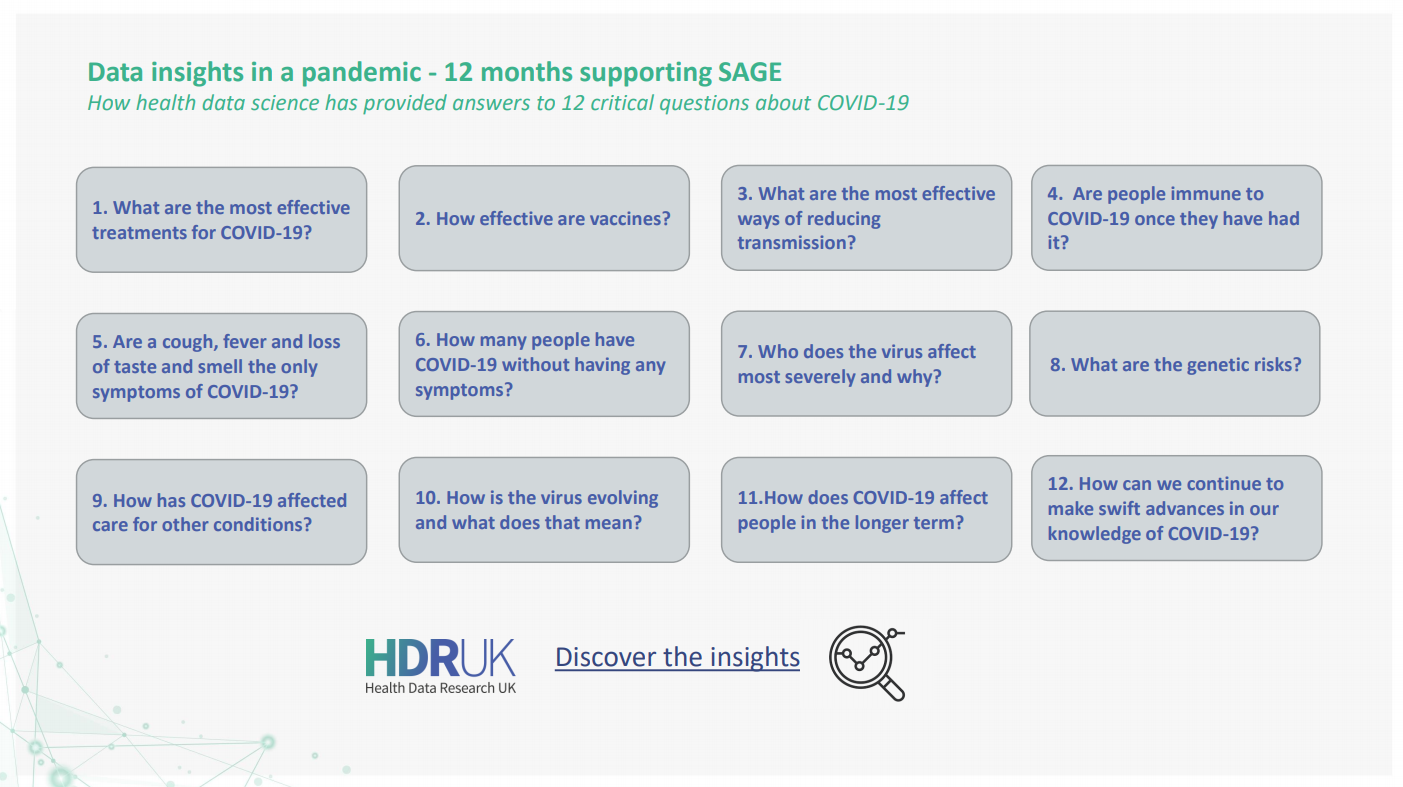

12 crucial questions about COVID-19 answered by health data research

22 April 2021

Data Insights in a Pandemic - 12 months of supporting SAGE

Expert analysis of health data has been central to tackling COVID-19 – showing us how we can reduce its spread, vaccinate against it, and how to most effectively treat people who fall seriously ill.

As the UK gradually emerges from lockdown, 12 months on from the first, there is now greater recognition of the contribution that health data science has made to the progress in tackling COVID-19. When cases first emerged in the UK, very little was known about this virus. Today we have evidence on who is most seriously impacted by COVID-19; how we can most effectively stop its spread, including through vaccines; and which drugs are most effective when people do become seriously ill with the virus.

Some of these breakthroughs have made unlikely household names of clinical trials and many epidemiologists. Perhaps less well-known is the work of the UK’s dedicated health data research community, which has enabled many of these discoveries to take place. By ensuring key datasets are made safely available, analysing those large quantities of data and converting that analysis into actionable insights, their work has formed the backbone of the UK’s ability to tackle the pandemic and keep people well.

The UK collects large quantities of health data. Used safely, it is a valuable asset. But the datasets are fragmented, residing in multiple locations, meaning it can be hard and time consuming for scientists to find and access.

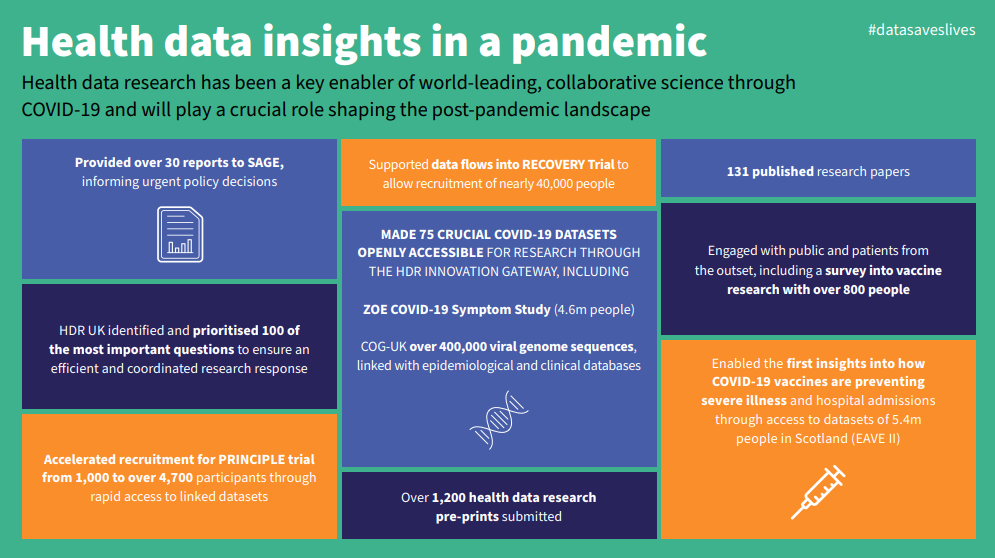

Health Data Research UK (HDR UK) – the country’s national institute for health data science – addresses these challenges, by uniting data and helping coordinate research efforts. In the past 12 months, it has made sure researchers can quickly access information relevant to COVID-19. This has enabled experts to make swift breakthroughs.

HDR UK has also ensured these findings are rapidly shared with national decision makers. The government’s Scientific Advisory Group on Emergencies (SAGE) has received 28 reports from HDR UK and its partners since April 2020. These reports detail the new datasets being made available and summarise key COVID-19 research. This means those influencing or making national policy have the information they need to make the best possible decisions.

“Data saves lives, as the pandemic has starkly illustrated. By continuing to bring the health research community together to use data in a trustworthy way– and engaging with members of the public – HDR UK will help shape the post-pandemic research landscape and support the future development of health data science, both in the UK and globally.”

Caroline Cake, Chief Executive, Health Data Research UK

To find out more about how health data science has been central to tackling COVID-19, sign up for HDR UK’s annual Scientific Conference Data Insights in a Pandemic on 23 June and our National Core Studies Symposium on 24 June.

Twelve important questions health data research has helped answer:

1. What are the most effective treatments for severe COVID-19?

For hospitalised patients:

Dexamethasone – arguably the research breakthrough of the last 12 months from RECOVERY as a unique, data-enabled trial that came together at breakneck speed, using data via NHS DigiTrials, based on:

- Rapidly expediated data governance

- Expertise provided by HDR UK’s data-enabled Clinical Trials work developed over the previous two years

- We also know that tocilizumab reduces the risk of death in patients who are hospitalised with severe COVID-19; and that sarilumab does the same. These studies informed updated guidance recommending the use of tocilizumab for any patient admitted to intensive care with COVID-19.

Non-hospitalised patients: Another HDR UK supported, data-enabled trial – PRINCIPLE – has provided the insight that asthma drug budesonide shortens recovery time in non-hospitalised patients.

2. How effective are vaccines against COVID-19?

Thanks to health data researchers working at pace, including those supported by HDR UK, we were able to know as quickly as 22 February that the vaccines scientists have developed against COVID-19 are effective:

- A single dose of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine is 94% effective against COVID-19 related hospitalisation

- A single dose of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine is 85% effective against COVID-19 related hospitalisation

- The Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine reduces infection rates by 75% after a single dose

- Older people who have been vaccinated are 50% less likely to be hospitalised or die due to COVID-19

We also know that vaccination rates are lower in people from an ethnic minority background, who live in areas of higher deprivation, and who have severe mental illness or learning disabilities. This helps healthcare leaders understand where they will need to make special efforts to encourage vaccine uptake.

Thankfully, we also know that this can change. Data from over 20,000 adults as part of the VirusWatch household study indicate that 86% of participants who were reluctant or intending to refuse a COVID-19 vaccine in December were planning on accepting (or already had accepted) a vaccine in February – and these findings were consistent across ethnic and social groups. This shift in attitude highlights the need to offer vaccines repeatedly as people change their minds over time.

3. What are the most effective ways of reducing transmission of COVID-19?

So long as strict mitigation measures were in place, teachers in Wales and in England were shown to have been at no increased risk of COVID-19 infection as schools reopened.

4. Are people immune to COVID-19 once they have had it?

It seems antibodies from COVID-19 provide some immunity to reinfection, lasting for at least five months. But antibody levels have been shown to decrease fairly quickly, particularly in younger adults and those who had no symptoms.

5. Are a cough, fever and loss of taste and smell the only symptoms of COVID-19?

Research has shown chills, loss of appetite, headache and muscle ache are also strongly linked with COVID-19 infection.

6. How many people have COVID-19 without having any symptoms?

This shows that even people who feel well may have the virus and be at risk of spreading it to others.

7. Who does the virus affect most severely and why?

Research has shown us that certain groups are much more likely to be badly affected by the virus. This includes:

- People with intellectual disabilities

- People who are older, male, overweight or from a deprived background

- People who have migrated to high income countries

- Orthodox Jewish populations (a study suggested an infection rate of five times the estimated national rate)

We also know that people from black and minority ethnic backgrounds are at higher risk, though the level of risk has changed as the pandemic has progressed.

And health data research has revealed some of the reasons these groups might be more at risk from COVID-19. The use of new large datasets, in this case the ZOE Covid Symptom Study (validated by further key datasets such as ONS Community Infection Survey), have been able to shed light on the geographic incidence of the virus, helping to detect rapid case increases in regions where government testing provision was lower. Such data provides an agile resource, part of a basket of indicators being used by policy makers during a quickly moving pandemic.

8. What are the genetic risks?

We know about genetic risks too. And not just increased risk – data from over 2000 participants of the Genetics Of Mortality In Critical Care (GenOMICC) and the International Severe Acute Respiratory Infection Consortium (ISARIC) Coronavirus Clinical Characterisation Consortium (4C) (ISARIC 4C) studies indicate that a common variant of the protein occurring in approximately 25% of the population is associated with a reduced likelihood of developing severe COVID-19 – suggesting that this protein (TMPRSS2) is a promising drug target in the treatment of COVID-19.

9. How has COVID-19 affected care for other conditions?

Using large-scale datasets from HDR UK hubs including Data-CAN and the BHF Data Science Centre, health data research has shown that:

- There were fewer interactions with GPs during the first part of the pandemic

- There have been decreases in heart disease referrals, diagnoses and treatment

- There have been reductions in referrals for suspected cancer – including colorectal cancer

- There have been decreases in the number of people attending chemotherapy appointments and impact on radiotherapy treatment too

- There is a growing backlog of endoscopic procedures such as colonoscopies that could take more than a year to clear

All of this is important in helping healthcare leaders plan services and care for those living with other serious illnesses during the pandemic.

10. How is the virus evolving and what does that mean?

The UK has carried out nearly half of all the world’s genome sequencing of COVID-19 – which is crucial part of our intelligence about the virus. The UK’s genuine global leadership in genomics is largely thanks to the incredible work of the COVID-19 Genomics UK Consortium “COG-UK”, led by Professor Sharon Peacock with the support of HDR UK project management and research expertise in understanding the cause of diseases. Their impact includes, among many other discoveries, the identification of new strains of COVID-19, including the B.1.1.7 (“British” or “Kent”) variant.

Research from Imperial College London and the CMMID COVID-19 Working Group showed the B.1.1.7 (“British” or “Kent”) variant is 50% more transmissible, which is important in understanding the current and future danger presented by the virus.

11.How does COVID-19 affect people in the longer term?

- We know there is an increased risk of mortality even following a hospital stay for COVID-19 and a need for further research into the long-term impact of the virus.

- A social media survey of 2550 people, co-produced with people living with long COVID, found that long Covid affected respondents daily life including their mental health, work, and domestic chores. For the majority, symptoms such as exhaustion, breathlessness, headache, and chest pressure/tightness fluctuate or relapse and common triggers include physical activity, stress, sleep disturbance and cognitive activity.

- Patient reported outcomes from 1,000 people discharged from hospital following treatment for COVID-19, revealed most survivors are not fully recovered five months after discharge – around 1 in 5 people developed a new disability, stopped working or changed jobs due to their health, and/or experienced symptoms of anxiety or depression.

12. How can we continue to make swift advances in our knowledge of COVID-19?

Researchers have used data to more rapidly recruit people to clinical trials. The accelerated recruitment to trials such as RECOVERY and PRINCIPLE has been one of the undoubted success stories to have emerged from a global health crisis; and will surely be one of the enduring aspects that will continue to be of benefit for years to come.

For now, continuing to use these techniques – the application of large-scale datasets to support recruitment and maintain participation in these trials – will be key to advance our understanding of how best to prevent and treat COVID-19.